A recent global assessment of shark populations at 371 coral reefs in 58 countries found no sharks at almost 20% of reefs and alarmingly low numbers at many others.

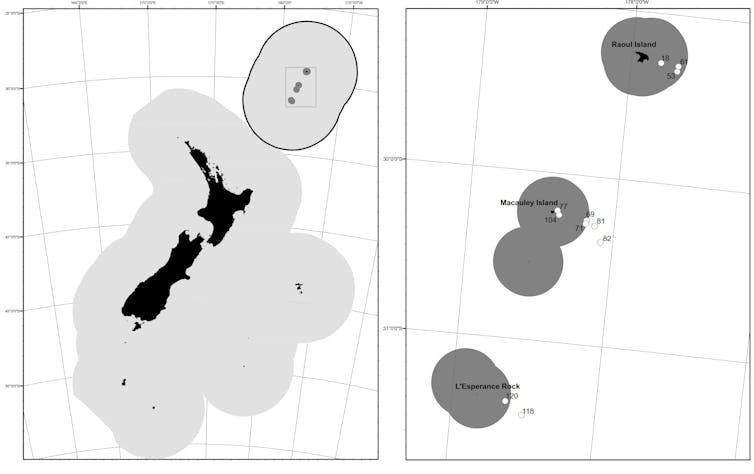

The study, which involved over 100 scientists under the Global FinPrint project, gave New Zealand a good score card. But because it focused on coral reefs, it included only one region — Rangitāhua (Kermadec Islands), a pristine subtropical archipelago surrounded by New Zealand’s largest marine reserve.

It is a different story around the main islands of New Zealand. Many coastal shark species may be in decline, and less than half a percent of territorial waters is protected by marine reserves.

Read more:

Scientists at work: Uncovering the mystery of when and where sharks give birth

Sharks in Aotearoa

In New Zealand, there are more than a hundred species of sharks, rays and chimaeras. They belong to a group of fishes called chondrichthyans, which have skeletons of cartilage instead of bone.

Some 55% of New Zealand’s chondrichthyan species are listed as “not threatened” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Not so encouraging is the 32% of species listed as “data deficient”, meaning we don’t know the status of their populations. Most species (77%) live in waters deeper than 200 metres.

Seven species are fully protected under the Wildlife Act 1953. They are mostly large, migratory species such as the giant manta ray. Some are threatened with extinction according to the IUCN, including great white sharks, basking sharks, whale sharks and oceanic white tip sharks.

Martin Prochazkacz/Shutterstock

Historically, basking sharks were caught as bycatch in New Zealand fisheries, and seen in their hundreds in some inshore areas. Sightings of these giant plankton-feeders suddenly dried up over a decade ago. We don’t know why.

Commercial shark fisheries

Eleven chondrichthyan species are fished commercially in New Zealand under the quota management system. Commercial fisheries for school shark, rig and elephant fish took off from the 1970s and now catch around 8,000 tonnes per year in total.

Finning of sharks has been illegal throughout New Zealand since 2014.

Most of New Zealand’s shark fisheries are considered sustainable. But a sustainable fishery can mean sustained at low levels, and we must tread carefully. School shark was recently added to the critically endangered list after the collapse of fisheries in Australia and elsewhere, and there’s a lot we don’t know about the New Zealand population.

We do know sharks were much more abundant in pre-European times. In Tīkapa Moana (Hauraki Gulf), sharks have since declined by an estimated 86%. An ongoing planning process provides some hope for the ecosystems of the gulf.

Protecting sharks

Not surprisingly, the global assessment found a ban on shark fishing to be the most effective intervention to protect sharks. Several countries have recently established large shark sanctuaries, sometimes covering entire exclusive economic zones.

These countries tend to have ecotourism industries that provide economic incentives for protection — live sharks can be more valuable than dead ones.

Other effective interventions are restrictions on fishing gear, such as longlines and set nets.

Waters within 12 nautical miles of the Kermadec Islands have been protected by a marine reserve since 1990. In 2015, the Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary was announced but progress has stalled. The sanctuary would extend the boundaries to the exclusive economic zone, some 200 nautical miles offshore, and increase the protected area 83-fold.

A large population of Galapagos sharks, which prefer isolated islands surrounded by deep ocean, thrive around the Kermadec Islands but are found nowhere else in New Zealand. Great white sharks also visit en route to the tropics. Many other species are found only at the Kermadecs, including three sharks and a sex-changing giant limpet as big as a saucer.

Author provided

New technologies are revealing sharks’ secrets

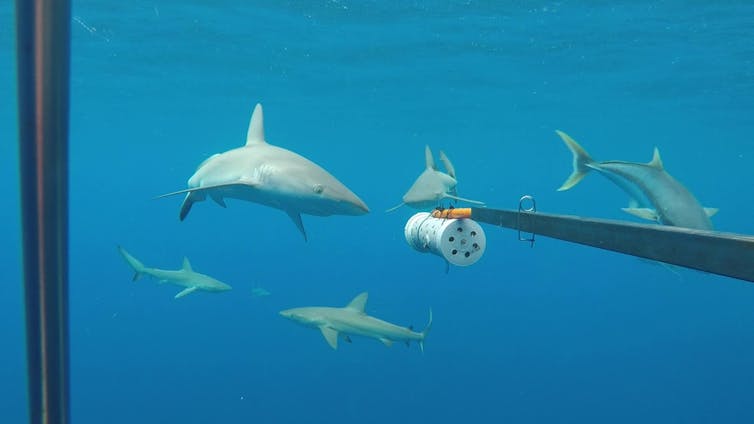

What makes the Global FinPrint project so valuable is that it uses a standard survey method, allowing data to be compared across the globe. The method uses a video camera pointed at a canister of bait. This contraption is put on the seafloor for an hour, then we watch the videos and count the sharks.

Baited cameras have been used in a few places in New Zealand but there are no systematic surveys at a national scale. We lack fundamental knowledge about the distribution and abundance of sharks in our coastal waters, and how they compare to the rest of the world.

Satellite tags are another technological boon for shark research. It is difficult to protect sharks without knowing where they go and what habitats they use. Electronic tags that transmit positional data via satellite can be attached to live sharks, revealing the details of their movements. Some have crossed oceans.

Sharks have patrolled the seas for more than 400 million years. In a few decades, demand for shark meat and fins has reduced their numbers by around 90%.

Sharks are generally more vulnerable to exploitation than other fishes. While a young bony fish can release tens of millions of eggs in a day, mature sharks lay a few eggs or give birth to a few live young. Females take many years to reach sexual maturity and, in some species, only reproduce once every two or three years.

These biological characteristics mean their populations are quick to collapse and slow to rebuild. They need careful management informed by science. It’s time New Zealand put more resources into understanding our oldest and most vulnerable fishes, and the far-flung subtropical waters in which they rule.![]()

Adam Smith, Senior Lecturer in Statistics, Massey University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.