USA: California

Shutterstock

Madeline Taylor, University of Sydney and Susan M Park, University of Sydney

Last week San Francisco became the latest city to ban natural gas in new buildings. The legislation will see all new construction, other than restaurants, use electric power only from June 2021, to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

San Francisco has now joined other US cities in banning natural gas in new homes. The move is in stark contrast to the direction of energy policy in Australia, where the Morrison government seems stuck in reverse: spruiking a gas-led economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Natural gas provides about 26% of energy consumed in Australia — but it’s clearly on the way out. It’s time for a serious rethink on the way many of us cook and heat our homes.

San Francisco is rapidly increasing renewable-powered electricity to meet its target of 100% clean energy by 2030. Currently, renewables power 70% of the city’s electricity.

The ban on gas came shortly after San Francisco’s mayor London Breed announced all commercial buildings over 50,000 square feet must run on 100% renewable electricity by 2022.

Buildings are particularly in focus because 44% of San Franciscos’ citywide emissions come from the building sector alone.

Read more:

4 reasons why a gas-led economic recovery is a terrible, naïve idea

Following this, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors unanimously passed the ban on gas in buildings. They cited the potency of methane as a greenhouse gas, and recognised that natural gas is a major source of indoor air pollution, leading to improved public health outcomes.

From January 1, 2021, no new building permits will be issued unless constructing an “All-Electric Building”. This means installation of natural gas piping systems, fixtures and/or infrastructure will be banned, unless it is a commercial food service establishment.

In the shift to zero-emissions economies, transitioning our power grids to renewable energy has been the subject of much focus. But buildings produce 25% of Australia’s emissions, and the sector must also do some heavy lifting.

A report by the Grattan Institute this week recommended a moratorium on new household gas connections, similar to what’s been imposed in San Francisco.

The report said natural gas will inevitably decline as an energy source for industry and homes in Australia. This is partly due to economics — as most low-cost gas on Australia’s east coast has been burnt.

Read more:

A third of our waste comes from buildings. This one’s designed for reuse and cuts emissions by 88%

There’s also an environmental imperative, because Australia must slash its fossil fuel emissions to address climate change.

While acknowledging natural gas is widely used in Australian homes, the report said “this must change in coming years”. It went on:

This will be confronting for many people, because changing the cooktops on which many of us make dinner is more personal than switching from fossil fuel to renewable electricity.

The report said space heating is by far the largest use of gas by Australian households, at about 60%. In the cold climates of Victoria and the ACT, many homes have central gas heaters. Homes in these jurisdictions use much more gas than other states.

By contrast, all-electric homes with efficient appliances produce fewer emissions than homes with gas, the report said.

Australia’s states and territories have much work to do if they hope to decarbonise our building sector, including reducing the use of gas in homes.

In 2019, Australia’s federal and state energy ministers committed to a national plan towards zero-carbon buildings for Australia. The measures included “energy smart” buildings with on-site renewable energy generation and storage and, eventually, green hydrogen to replace gas.

The plan also involved better disclosure of a building’s energy performance. To date, Australia’s states and territories have largely focused on voluntary green energy rating tools, such as the National Australian Built Environment Rating System. This measures factors such as energy efficiency, water usage and waste management in existing buildings.

But in 2020, just 2% of buildings in Australia achieved the highest six-star rating. Clearly, the voluntary system has done little to encourage the switch to clean energy.

The National Construction Code requires mandatory compliance with energy efficiency standards for new buildings. However, the code takes a technology neutral approach and does not require buildings to install zero-carbon energy “in the absence of an explicit energy policy commitment by governments regarding the future use of gas”.

An estimated 200,000 new homes are built in Australia each year. This represents an opportunity for states and territories to create mandatory clean energy requirements while reaching their respective net-zero emissions climate targets.

Under a gas ban, the use of zero-carbon energy sources in buildings would increase, similar to San Francisco. This has been recognised by Environment Victoria, which notes

A simple first step […] to start reducing Victoria’s dependence on gas is banning gas connections for new homes.

Creating incentives for alternatives to gas may be another approach, such as offering rebates for homes that switch to electrical appliances. The ACT is actively encouraging consumers to transition from gas.

Read more:

Australia has plenty of gas, but our bills are ridiculous. The market is broken

Banning gas in buildings could be an economically sensible move. As the Grattan Report found, “households that move into a new all-electric house with efficient appliances will save money compared to an equivalent dual-fuel house”.

Meanwhile, ARENA confirmed electricity from solar and wind provide the lowest levelised cost of electricity, due to the increasing cost of east coast gas in Australia.

Future-proofing new buildings will require extensive work, let alone replacing exiting gas inputs and fixtures in existing buildings. Yet efficient electric appliances can save the average NSW homeowner around A$400 a year.

Learning to live sustainability, and becoming resilient in the face of climate change, is well worth the cost and effort.

Recently, a suite of our major gas importers — China, South Korea and Japan — all pledged to reach net-zero emissions by either 2050 or 2060. This will leave our export-focused gas industry possibly turning to the domestic market for new gas hookups.

But continuing Australia’s gas production will increase greenhouse gas emissions, and few Australians support an economic recovery pinned on gas.

The window to address dangerous climate change is fast closing. We must urgently seek alternatives to burning fossil fuels, and there’s no better place to start that change than in our own homes.

Madeline Taylor, Lecturer, University of Sydney and Susan M Park, Professor of Global Governance, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Richard Aster, Colorado State University

California earthquakes are a geologic inevitability. The state straddles the North American and Pacific tectonic plates and is crisscrossed by the San Andreas and other active fault systems. The magnitude 7.9 earthquake that struck off Alaska’s Kodiak Island on Jan. 23, 2018 was just the latest reminder of major seismic activity along the Pacific Rim.

Tragic quakes that occurred in 2017 near the Iran-Iraq border and in central Mexico, with magnitudes of 7.3 and 7.1, respectively, are well within the range of earthquake sizes that have a high likelihood of occurring in highly populated parts of California during the next few decades.

The earthquake situation in California is actually more dire than people who aren’t seismologists like myself may realize. Although many Californians can recount experiencing an earthquake, most have never personally experienced a strong one. For major events, with magnitudes of 7 or greater, California is actually in an earthquake drought. Multiple segments of the expansive San Andreas Fault system are now sufficiently stressed to produce large and damaging events.

The good news is that earthquake readiness is part of the state’s culture, and earthquake science is advancing – including much improved simulations of large quake effects and development of an early warning system for the Pacific coast.

California occupies a central place in the history of seismology. The April 18, 1906 San Francisco earthquake (magnitude 7.8) was pivotal to both earthquake hazard awareness and the development of earthquake science – including the fundamental insight that earthquakes arise from faults that abruptly rupture and slip. The San Andreas Fault slipped by as much as 20 feet (six meters) in this earthquake.

Although ground-shaking damage was severe in many places along the nearly 310-mile (500-kilometer) fault rupture, much of San Francisco was actually destroyed by the subsequent fire, due to the large number of ignition points and a breakdown in emergency services. That scenario continues to haunt earthquake response planners. Consider what might happen if a major earthquake were to strike Los Angeles during fire season.

Northridge earthquake, Jan. 17, 1994.

Robert A. Eplett/FEMA

When a major earthquake occurs anywhere on the planet, modern global seismographic networks and rapid response protocols now enable scientists, emergency responders and the public to assess it quickly – typically, within tens of minutes or less – including location, magnitude, ground motion and estimated casualties and property losses. And by studying the buildup of stresses along mapped faults, past earthquake history, and other data and modeling, we can forecast likelihoods and magnitudes of earthquakes over long time periods in California and elsewhere.

However, the interplay of stresses and faults in the Earth is dauntingly chaotic. And even with continuing advances in basic research and ever-improving data, laboratory and theoretical studies, there are no known reliable and universal precursory phenomena to suggest that the time, location and size of individual large earthquakes can be predicted.

Major earthquakes thus typically occur with no immediate warning whatsoever, and mitigating risks requires sustained readiness and resource commitments. This can pose serious challenges, since cities and nations may thrive for many decades or longer without experiencing major earthquakes.

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake was the last quake greater than magnitude 7 to occur on the San Andreas Fault system. The inexorable motions of plate tectonics mean that every year, strands of the fault system accumulate stresses that correspond to a seismic slip of millimeters to centimeters. Eventually, these stresses will be released suddenly in earthquakes.

But the central-southern stretch of the San Andreas Fault has not slipped since 1857, and the southernmost segment may not have ruptured since 1680. The highly urbanized Hayward Fault in the East Bay region has not generated a major earthquake since 1868.

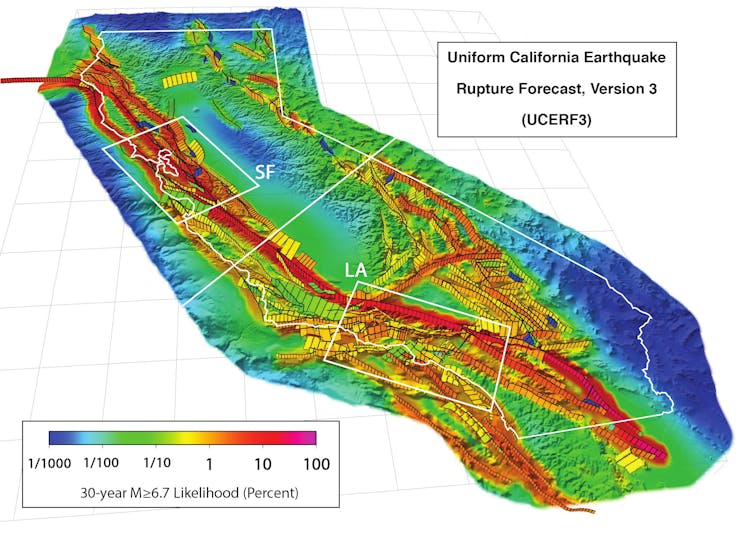

Reflecting this deficit, the Uniform California Earthquake Rupture Forecast estimates that there is a 93 percent probability of a 7.0 or larger earthquake occurring in the Golden State region by 2045, with the highest probabilities occurring along the San Andreas Fault system.

California’s population has grown more than 20-fold since the 1906 earthquake and currently is close to 40 million. Many residents and all state emergency managers are widely engaged in earthquake readiness and planning. These preparations are among the most advanced in the world.

For the general public, preparations include participating in drills like the Great California Shakeout, held annually since 2008, and preparing for earthquakes and other natural hazards with home and car disaster kits and a family disaster plan.

No California earthquake since the 1933 Long Beach event (6.4) has killed more than 100 people. Quakes in 1971 (San Fernando, 6.7); 1989 (Loma Prieta; 6.9); 1994 (Northridge; 6.7); and 2014 (South Napa; 6.0) each caused more than US$1 billion in property damage, but fatalities in each event were, remarkably, dozens or less. Strong and proactive implementation of seismically informed building codes and other preparations and emergency planning in California saved scores of lives in these medium-sized earthquakes. Any of them could have been disastrous in less-prepared nations.

Nonetheless, California’s infrastructure, response planning and general preparedness will doubtlessly be tested when the inevitable and long-delayed “big ones” occur along the San Andreas Fault system. Ultimate damage and casualty levels are hard to project, and hinge on the severity of associated hazards such as landslides and fires.

Several nations and regions now have or are developing earthquake early warning systems, which use early detected ground motion near a quake’s origin to alert more distant populations before strong seismic shaking arrives. This permits rapid responses that can reduce infrastructure damage. Such systems provide warning times of up to tens of seconds in the most favorable circumstances, but the notice will likely be shorter than this for many California earthquakes.

Early warning systems are operational now in Japan, Taiwan, Mexico and Romania. Systems in California and the Pacific Northwest are presently under development with early versions in operation. Earthquake early warning is by no means a panacea for saving lives and property, but it represents a significant step toward improving earthquake safety and awareness along the West Coast.

![]() Managing earthquake risk requires a resilient system of social awareness, education and communications, coupled with effective short- and long-term responses and implemented within an optimally safe built environment. As California prepares for large earthquakes after a hiatus of more than a century, the clock is ticking.

Managing earthquake risk requires a resilient system of social awareness, education and communications, coupled with effective short- and long-term responses and implemented within an optimally safe built environment. As California prepares for large earthquakes after a hiatus of more than a century, the clock is ticking.

Richard Aster, Professor of Geophysics, Colorado State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.